The Prancing Deer (Part I)

History of the Russian automobile from its humble beginnings to the October Revolution and its massive growth under the five year plans. First part of a two-post series on the Russian automobile.

Russia's automotive industry has a rich and vast history, playing the roles of both a pioneer and a global competitor. Yet, despite competing with more industrial powers through the early 20th century and making strides in the Cold War, today, the veteran industry is not among the greats. It does not even enjoy a public opinion formulated on its legacy as a pioneer. Instead, the industry that survived two world wars, a communist revolution, relocations, and isolation from the richest markets in the world is seen as lesser than its global counterparts and forced to live in the shadow of a simple question - “Where did Russian automobiles fail?”

This piece will take you from the early beginnings of the Russian automotive industry to the October Revolution and the start of the Second World War. It is the first of two parts in a series on Russia’s automotive industry and act as a background to the later Soviet period and then the promise and subsequent failure in the current independence era.

Tsarist Beginnings

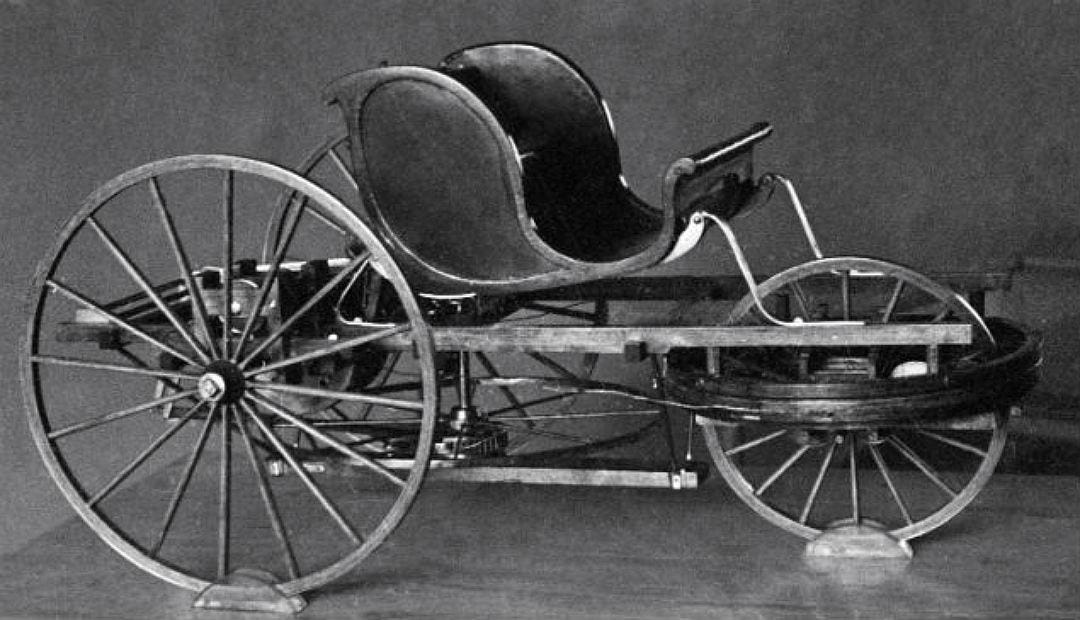

Similar to Russian aviation, the history of the automotive industry starts with a chapter in Tsarist Russia’s late industrialization and collapse. While the vast majority of this period occurred between the very late 19th and early 20th century, some pioneers appeared much earlier. The first car that did not utilize animal propulsion was the samokatka (which translates to Self-Roller) invented by the legendary and self-taught Ivan Kulibin in 1779, which is widely regarded as the earliest example of Russia’s automotive industry. Kulibin’s cart is one of the candidates for the “first automobile,” as it employed a gearbox and flywheel, amongst several other car-like characteristics except mechanical propulsion. Kulibin has become so famous for his self-taught education and enthusiasm that his name is now a term in Russian society for amateur inventors.

Kulibin’s efforts were followed by a long period of inactivity and stagnation. The government found itself uninterested in the prospect of road transportation and, as the industrial revolution developed, instead invested in much more needed rail transportation to tie the vast nation together. While various pioneers and tinkerers still made progress in and around the field, it was not until the late half of the 19th century that excitement about the topic began returning, with the first road-focused steam vehicle being invented in the 1860s. The Russian government became interested in the military prospects of such vehicles - which is a very common and necessary sign in any of Imperial Russia’s remotely successful industries - and purchased several foreign engines from Britain to test their military applications.

By the time of the Russo-Turkish War of 1878, which saw the collapse of any notable Ottoman influence in the Balkans, the Russian army had purchased ten foreign-made engines (tractors) and two domestic variants from Maltsev - a locomotive factory founded by a Russian general. The success of the domestic engines, having been built off of the British model to the point of near-perfect component interchangeability, was a topic of much excitement in Russian military circles. Overall, the war saw the first-ever use of mechanical transportation in the military, which also proved to be financially and logistically successful.

The first Russian automobile with an internal combustion engine, a crucial leap from the Maltsev tractor, was the 1896 Yakovlev & Freze, ushering in the age of proper automobiles into Russia’s economy. The Y&F was a very experimental vehicle constructed in Yakolev’s machining factory, and all of its prospects ended when Evgeny Aleksandrovich Yakovlev died abruptly in 1898.

Meet the Makers

At the beginning of the 21st century, automotive manufacturing was split between multiple factories. Russo-Balt (Russo-Baltic Waggon Works) was by far the most notable and successful of the automobile manufacturers of Tsarist Russia. Its impact was felt in many other areas of the Empire’s industries, from aviation to railway equipment. The company gained a reputation for excellence even among foreigners. In parallel to my previous post on aviation, the factory even employed Igor Sikorsky, who designed multiple aircraft, including the Ilya Muromets, widely regarded as the best bomber of the First World War and the backbone of the Tsarist section of the aforementioned post. Only one of these planes was lost in a battle with four German fighters, three of which it shot down and the fourth returned with heavy damages.

Russo-Balt opened its automotive divisions in 1909, thirteen years after the Yakovlev & Freze, after a Belgian engineer was hired as the Chief Engineer and Designer for the motorcar department, with the first Russo-Balt car - the S24/30, rolling out in May 1909. Like other company products, the car was a solid product that wielded an amount of foreign prestige. The prestige of the car was greatly increased after it came in third at the St. Petersburg-Riga race. The race had a number of leading foreign manufacturers, and the victory affirmed the place of Russia’s industry among the global standard. Russo-Balt continued to innovate with new, progressively better variants of their cars which resulted in the S24/40-18. Production of the 18th Series was delayed as the factory fled its facility in Riga, modern-day Latvia, to St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1915 to escape the German advance.

It should be noted that the bodies of Russian automobiles were nearly always superior to foreign variants as they were built for the harsher road conditions in the Empire, as even the best foreign examples could hardly persist on Russia’s roads.

The Great War

The Great War was an existential crisis for the Imperial government and thus, both the flow of money to automakers and the innovative capacity built up over the past years resulted in a number of notable vehicles and designs. The Imperial Garage itself even led multiple innovations with its French commander, Adolphe Kégresse (who was also Tsar Nicholas II’s personal chauffeur) inventing the half-track. Kégresse had a personal mission of creating a cross-country vehicle that would be able to traverse all of Russia’s vast terrain and conditions, which led him to invent the “Kégresse track,” allowing for the conversion of the Garage’s Russo-Balt S24/30s into half-tracks. This resulted in the world’s first ATV. Kégresse later continued using his system to manufacture various vehicles for the war effort.

Using Kégresse’s invention, the Putilov factory in St. Petersburg successfully converted British Austin armored cars into Austin-Putilov half-tracks adapted for the brutal conditions of the Eastern front. By 1917, the Putilov factory, which already had a powerful legacy of railroad production and shipbuilding (even constructing multiple submarines,) used wartime production of the Austin-Putilov cars and other military goods to become the largest enterprise in the capital city of the Empire, until eventually being the site of the 1917 Putilov strikes that were crucial steps in the February revolution.

Russia’s First Tanks

As the First World War introduced the world’s militaries to the first implementation of tanks in combat, the Russian Empire pursued its own models. This pursuit can be summed up in the three most prominent models of the Tsarist Empire: the Mendeleev Tank, Vezdekhod Tank, and Tzar Tank. Out of the three, only the latter and worst variant saw any experimentation, and none appeared on the battlefield before the revolutions of 1917. These vehicles served as the precursor for the Soviet tank corps.

The Mendeleev tank was designed by Vasily Mendeleev, the son of the renowned Russian Scientist Dmitri Mendeleev, most known for his invention of the Periodic Table. The design could date back to 1898, making it one of the earliest formulations for a modern tank, especially for a super-heavy variant. Vasily’s naval engineering experience can be clearly seen in the armament. The frontal gun would be a 120mm Naval Gun, the largest of any Great War tank and the vast majority of any tanks seen in the Second World War. This gun would be equipped with various advanced concepts, from a recoil system and advanced elevation for its primary gun to a turret-based secondary machine gun, allowing the tank to operate as a mobile artillery platform. Many of its systems across its armament, propulsion, and construction were extremely advanced for the time and wouldn’t be seen until the Second World War. However, it failed to get any traction amongst the high command and was never granted even a prototype.

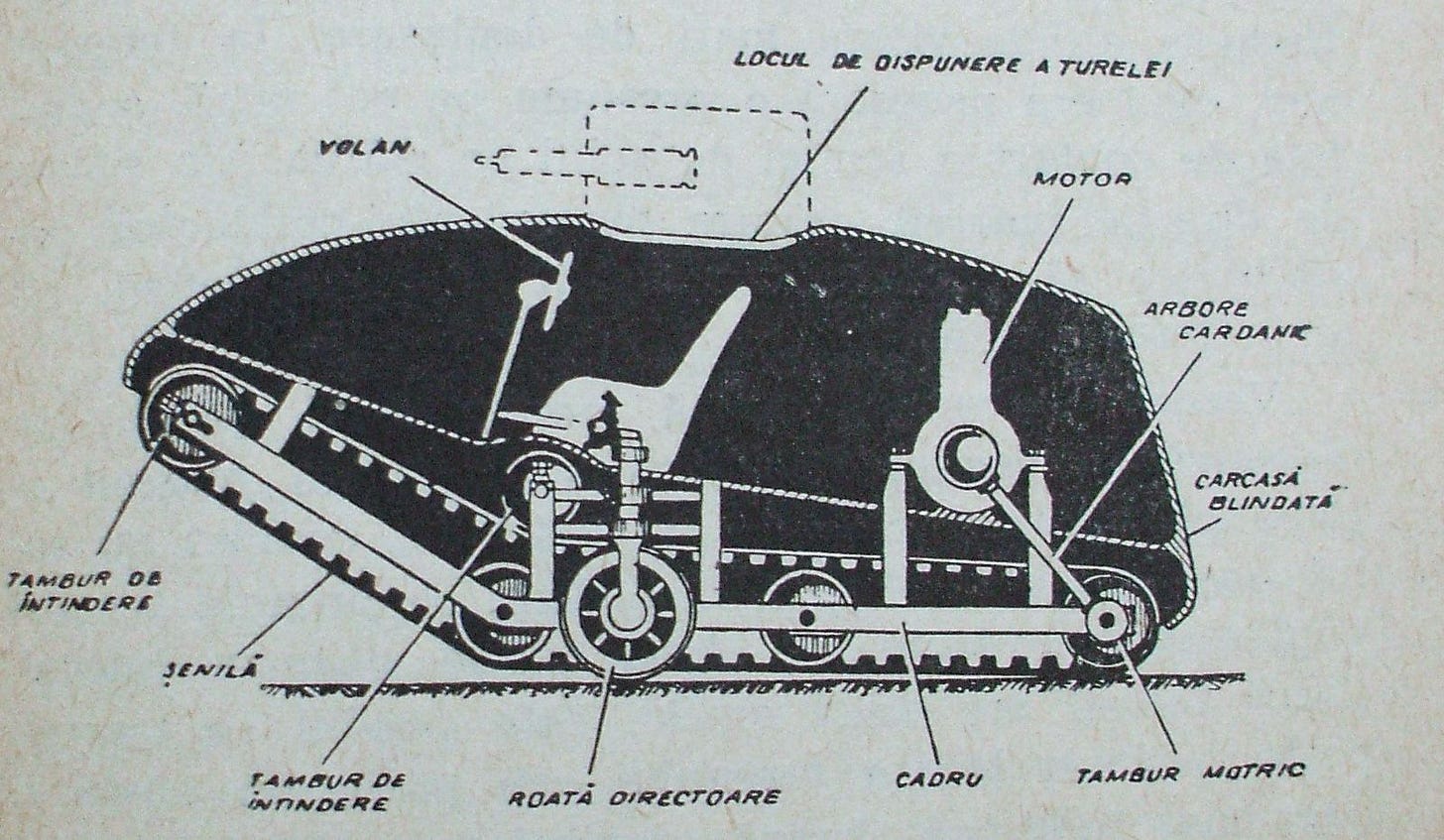

The Vezdekhod was the first modern tank prototype in the world. Airplane designer Aleksandr Porokhovschikov invented it as a response to Russia’s many successful armored cars and ATVs. It is one of the many candidates for the “world’s first tank.” It much closer resembled a standard tankette with various minor changes to its steering and is akin to the other Entente tankettes of the war. After the first stages of prototyping, the design was denied due to poor steering, with the “World’s First Tank” never firing a single shot on the battlefield or the test range. The attitude of the army to such experiments was incredibly apathetic.

Finally, the Tsar Tank is the most famous of Russia’s great war vehicles and the only one to ever be truly considered by the high command. Its story begins when military engineer Nikolay Lebedenko gifted a model of the now infamous vehicle to Tsar Nicholas II. After that, the Emperor and a palace engineer tested the vehicle and were awed by its ability to overcome multiple books containing the Empire’s laws. Thus, funding was allocated to create a fully functional tank for testing. While the first life-sized variant was unbalanced and didn’t come equipped with proper engines - the Empire continued with the project, sponsoring the development of a new engine. The story of the Tsar Tank ended only with the 1917 revolution, after which Lebedenko fled abroad, and the tank was abandoned and eventually dismantled by the Communist regime, ending the lifetime of history’s largest-ever armored vehicle.

While all of these experiments failed, either due to the Imperial Army's apathy or, in the case of the Tsar Tank, its own technological imperfections, they showed that even the dying Empire could still produce brilliant and ahead-of-their-time designs. Both the Vezdekhod and the Mendeleev tanks promised to be either on par or superior to the variants produced by their Entente allies or Germany’s failed A7V tank.

However, the failure of the much more practical designs to attract attention within the military high command showcases where the stereotypes of Russia’s backwardness truly emerge - while the people were ready to innovate, the leadership refused. The Vezdekhod and Mendeleev tanks only gathered the funding for a small prototype or were denied, and both revolutionary designs spent the war in the trash bin of the collapsing Ministry of War. While their implementation wouldn’t have turned the tide of the war or prevented the collapse of the Tsar, a Russian government open to progress could’ve.

The Revolution & Boom Years

In October 1917, a culmination of the Tsarist mishandling of the country and the First World War resulted in the October Revolution, cementing the Bolsheviks into power and inaugurating a brutal civil war that drained government funds and resulted in massive death and immigration. The automotive industry had endured the Great War, emerging scared after losing its base in Riga, undergoing major changes as a result of the October Revolution, the Russian Civil War, and then a number of various conflicts by the USSR to reclaim various lands held by the preceding empire.

The aforementioned frontrunner of Russian car development, Russo-Balt, was nationalized by the Soviet government in 1918 and promptly renamed to Prombron. By 1921, any notable foreign car plants within the country were also placed under government control. It took until 1924 for the first fully Soviet-produced vehicles to roll off the production line at the Moscow Automobile Plant (AMO). In 1927, Soviet engineers designed an original Soviet civilian automobile for the first time. The first Soviet civilian automobile, the NAMI-1, was developed by the Scientific Automobile & Motor Institute (NAMI). The institute became the heart of development for the Soviet automobile industry, creating new cars, trolleybusses, and other civilian automotive equipment.

Starting in 1931, AMO1 began producing truck designs licensed from the US-based Autocar, and a newly opened plant in Nizhny Novgorod began producing cars under licenses secured from the famous Ford Motor Company. Both of these industries, amongst many others, were built or reconstructed during the Industrialization Boom experienced by the Soviet Union in the 30s. The government under Joseph Stalin agreed with the policy adopted by the fading Tsarist government in 1916 after the 1st World War, making apparent how crucial domestic car production was for the Russian state, and many new automotive plants were created. This laid the foundation for the Soviet Union to soar to the second place producer of trucks in the world, leaping ahead of the British Empire, France, and the 5-year-old Nazi Germany, with even a CIA report declassified in 2013 commenting on the vast success of the industry.

The plants constructed as part of the five-year plans, which were the vast majority of automobile factories in the Union, were disproportionately located in the industrial hubs of the Russian SFSR. Significant plans to develop the industry outside of the RSFSR were limited to the city of Kharkiv (then Kharkov) in Ukraine; however, they did not experience notable success and were complicated by the Holodomor. It would not be until the post-war recovery that the other SSRs saw these investments. By the 21st of June 1941, the Soviet Union had produced over one million automobiles and transformed the minor industry into a global behemoth. The biggest customer was the Red Army.

On the 22nd of June, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union without a declaration of war alongside Romania, Finland, Hungary, and Italy in the largest land offensive in human history. After 101 days, Fascist forces advanced over 600,000 square miles and began the Battle for Moscow.

1,314 days later, on the 9th of May, 1945, the German Reich unconditionally surrendered after the Red Army occupied Berlin, and Hitler committed suicide. A massive percentage of the Soviet Union’s most populated, fertile, and industrialized land was scorched, looted, and destroyed, as was much of Europe’s. Russia’s Prancing Deer is ready to be born in 1950 when the Gorky Automobile Plant (GAZ) changes its logo from a copy of Ford’s to the iconic animal.

As the deer dances in the 1950s, ahead of the industry is a series of majestic leaps and stumbles that will eventually lead it through various eras of the Soviet Union and its eventual dissolution to the current disastrous period under Putin. The period in which all the glory and hope of this industry, which had just begun recovery after the fall of the Soviet Union, was destroyed as foreign models, especially from China, filled the once-domestic market. This history will be expanded on greatly in the next part.

The invaluable sources used for this post included “Russian Motor Vehicles: The Czarist Period 1784 to 1917” by Maurice A. Kelly, which I found very interesting and informative for the exclusive piece of automotive history it is written on.

Since the fall of the Tsarist government, AMO has undergone multiple name changes. In 1920, it was renamed the First Government Automobile Plant (1GAZ), and in 1956, it was renamed after Stalin, with the abbreviation changed to ZIS. For simplicity purposes, and since the Soviets themselves referred to the plant as the “Former AMO” until 1956, I will continue to use AMO.